from Capterio

- Despite high levels of ambition, flaring is at a record high. We undertook a “flare perception survey” to explore why … and to identify how we can accelerate and scale action. Perceptions are key in today’s increasingly climate-conscious world.

- Our research confirmed that there are many benefits to reducing flaring (e.g. lower GHG emissions and higher revenue). But there are perceived challenges around economics, weak regulators and financing.

- Our data highlights key differences in perceptions between geographies. Respondents from Europe appear more focussed on emissions. Those from MENA and USA are more focussed on revenue, whilst respondents from North America are most focused on high technology solutions. Some of these perceptions are consistent with our on-the-ground experience. But many can be addressed.

- The findings from this research should help the oil and gas industry to unlock opportunities, accelerate deployment and scale for impact. Together we can move from perception to action.

Introducing our “Flare Perception Survey”

With increased pressure on “ESG”, the “energy transition”, decarbonisation and “net-zero”, flaring is rightly in focus. The urgency is apparent: flaring was up by 3% in 2019 (vs 2018), to 150 BCM per year leading to 1.2 billion CO2-equivalent tonnes of potentially avoidable emissions, despite commitments from many governments and companies to flare reduction programmes.

There is clearly a gap between “intent” and “execution” on flaring programmes – a sense of deadlock. Yet flare capture projects reduce emissions, create value and help to accelerate the energy transition. We need to unlock, accelerate and scale flare projects. A senior climate adviser from a leading IOC told us recently “we’ve been talking about flaring for years … we just haven’t prioritised actually solving it“.

To identify why change is slow – and what needs to happen to accelerate it – Capterio undertook some bespoke research. After all, perceptions matter – and rightly or wrongly, shape action. We aimed to generate a robust evidence base, test a few hypotheses and show how progress is possible.

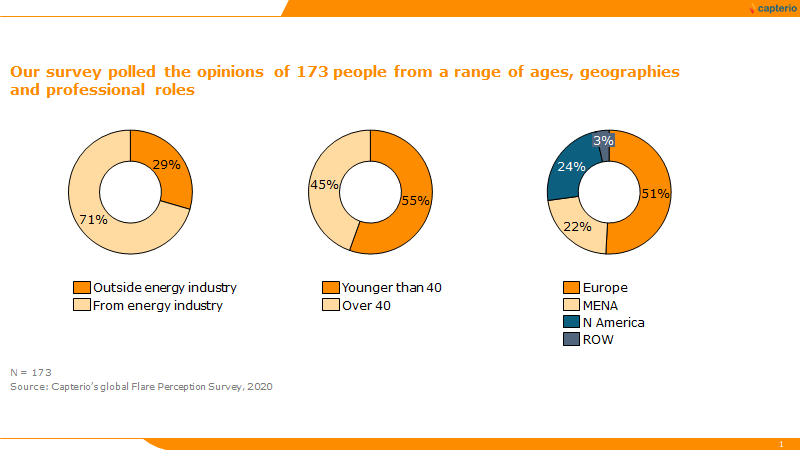

Our “Flare Perception Survey”, conducted in the spring/summer of 2020, polled 173 individuals across Europe, MENA, North America (and other) spanning a range of ages (from students to retirees) and from within and outside the energy industry.

We have analysed the data to explore how cohorts think, what language/arguments are likely to most resonate with particular stakeholder groups and how we might, as an industry, unlock the change we need (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Demographics behind our flare perception survey. A total of 173 respondents from within and outside the industry, across a range of ages and from a range of geographies.

In addition to some basic demographic data, the respondents were polled on three core subjective questions, “why does flaring happen?”, “what are the main benefits of reducing flaring“.

We asked respondents to “force rank” a set of multiple-choice options. The results presented are focussed on respondents from within the industry, but we highlight additional insights from the broader group where relevant.

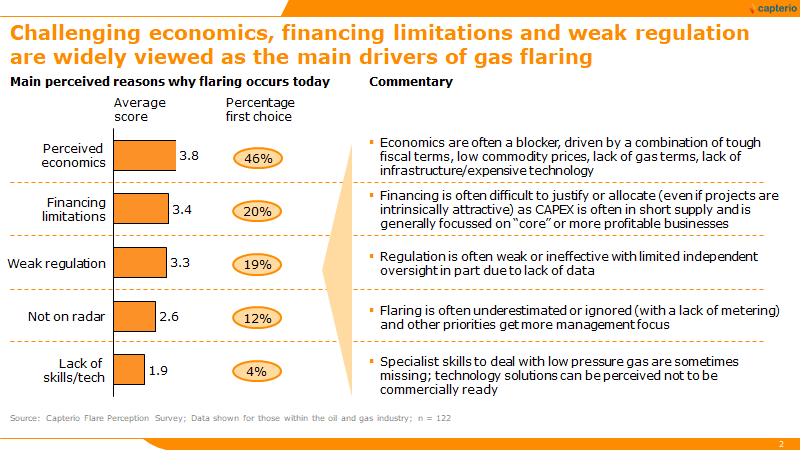

Question 1: “why does flaring happen?”

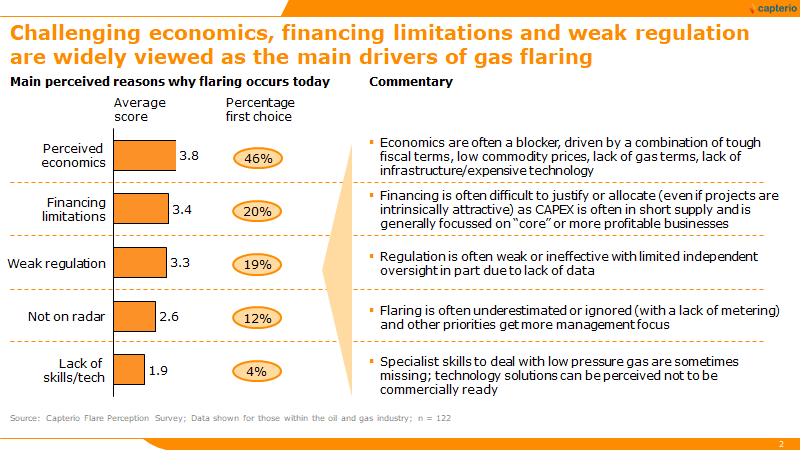

At a global level, we found challenges around economics, lack of financing and weak regulation were the main reasons why flaring occurs (Figure 2, left-hand side). Almost half of respondents believe that unattractive economics hinder progress.

Respondents generally scored “not on the radar” and “lack of skills/technology” lower. Figure 2 (right-hand side) outlines the main drivers of these perceptions.

Figure 2: Responses to the question “Why does flaring happen? Respondents were asked to force rank the 5 possible options from 1 (highest = most important) to 5 (lowest = least important). Left-hand chart shows the average global response by option. The top-ranked score is highlighted. The charts on the right show the variance in the average response between the selected region and the global average. Red bars highlight where the average score is lower (less of an issue) than the global average. Note that this data is for a subset of respondents from within the industry only although the relative scores from the wider group of respondents are very similar.

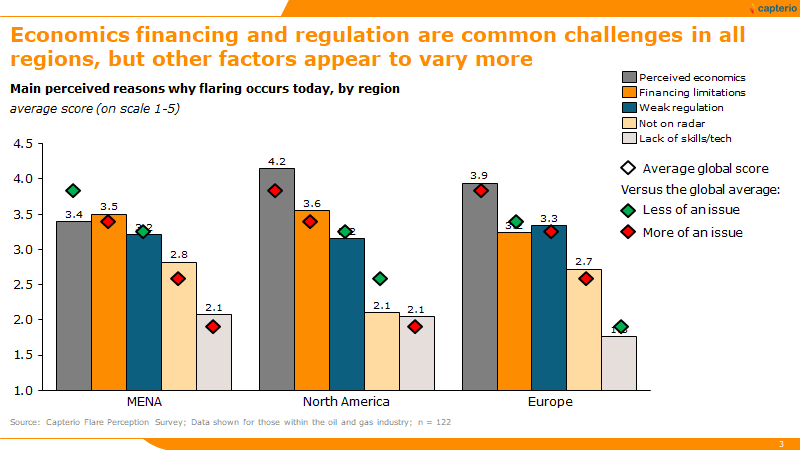

We were not surprised that 46% of respondents selected the answer “the economic incentives are not sufficient (it is uneconomic)” (but believe this is an unduly pessimistic perception), but what we found particularly interesting was the diversity of views between respondents from different regions (see Figure 3):

- Those in MENA rated “lack of financing” as the most significant barrier (also, this was the most popular first-choice response). We also compared the results in MENA to the global average. We found that “lack of economics” is much less of an issue than the global average (meaning that the economics are perceived to be more attractive than the global average – hence a large green diamond on the chart), whereas flaring was less “on the radar” than the global average, probably because the public discourse of issues around flaring is much less present.

- Conversely, North American respondents noted that “perceived economics” is a more significant factor than other geographies (no doubt because flares in the US and Canada are generally small, with 90% are lower than 2 million scf/day). Similarly, flaring is much more “on the radar” in this region versus the global average (no doubt because of the sharp focus on flaring – in part because of the role of the media and players such as EDF, and in part because some of the flaring is close to populated areas such as onshore Permian).

- Notably, European respondents believe that financing and technology/skills are significantly less of an issue than the global average, which we interpret as due to well-functioning markets and a well-developed set of applicable technologies.

- Finally, we note that younger people (those under 40) appear to be significantly more focussed on “weak regulation” as key determinant flaring – but there were no other significant differences.

Figure 3: Regional breakdown to the question “Why does flaring happen?” Diamonds indicate the average of the score across all regions and highlight the significant variances by region.

For completeness, we found no significant differences between the relative rankings by age group or between those in or out of the industry.

Why our analysis and insights sometimes challenge these perceptions:

- On economics: The finding that challenged economics is a significant perceived barrier today is not particularly surprising – it is a common (mis)conception. Our work in multiple countries has identified many highly attractive projects. Economics are significantly improved when commercial structures are innovated, technology is optimised, and real-time data (such as from our Global Flaring Intelligence Tool) is used to shape projects.

- On financing: The challenge of financing is also not unexpected: few oil and gas majors would naturally choose to allocate capital to flare capture projects – they are intuitively far more focussed on larger capital projects closer to their core business. Capital constraints are particularly likely in a post-COVID world, and especially within National Oil Companies (given the increasingly-strained national budgets). We do, however (now, more than ever) see tremendous potential for innovative players and new business models to fill the gap.

- On skills and capabilities: Most regions ranked low, suggesting that the market has, in general, no shortage of technical solutions to gas flaring. In our experience, the majority of the flared volume can be addressed with proven technologies.

One possible exception is North America, which our respondents felt had a more significant technology gap. Intuitively, given the small size and rapid decline of the flares in (e.g.) the Permian, Eagleford or Bakken, operators have a bias for looking for new and innovative technologies (e.g. mini GTL or mini LNG) to monetise their flaring.

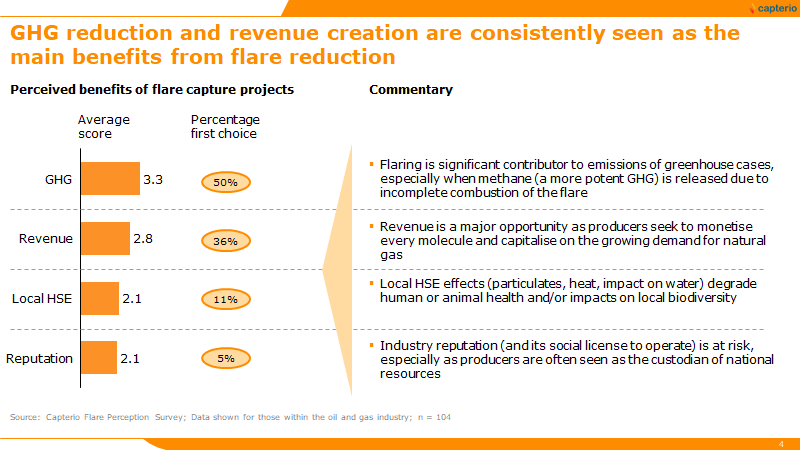

Question 2: “What are the main benefits of flare capture projects?”

At a global level, our survey found the main benefits of flaring were in reducing emissions and creating revenue (Figure 4, left-hand side). The local HSE impact of flaring (from heat, light and particulates) was lower ranked. Similarly, the “reputational” benefits were ranked lowest (presumably respondents view “reputation” as a consequence of better HSE/emissions performance). Figure 4 (right-hand side) has the details:

Figure 4: Responses to the question “What are the main benefits of reducing flaring?” Respondents were asked to force rank the 4 possible options from 1 (highest = most important) to 4 (lowest = least important). Left-hand chart shows the average global response by option. The charts on the right show the variance in the average response between the selected region and the global average. The top-ranked score is highlighted. Red bars highlight where the average score is lower (less of an issue) than the global average. Note this data is for a subset of respondents from within the industry only. Respondents from outside of the industry have place slightly higher relative emphasis on local HSE.

We found regional differences in the perceptions insightful (see also Figure 5):

- Respondents from the MENA and North America regions focus much less on GHG emissions than Europe, which are much more focussed on climate topics.

- Respondents from MENA region places significantly more focus on local HSE conditions versus the global average, whereas those from Europe focus less on flaring’s local impacts.

Figure 5: Regional breakdown to the question “What are the main benefits of flare capture projects?” Diamonds indicate the average of the score across all regions and highlight the significant variances by region.

Our interpretation

The difference in the relative importance of GHG vs revenue likely reflects the national priorities. MENA, being dominated by “petrostates” believe they need to prioritise economic rent over the climate (and perhaps even more so post-COVID).

Europe’s economy is, however, much more diversified and is better attuned to the “climate agenda”. North America’s relative increased emphasis on revenue probably talks to the potential difficulties of making flare projects sufficiently economically-attractive – partly because flares in this region tend to be small.

Implications for flare capture projects: what does it all mean?

Not all the perceptions observed above equate to the reality we have seen on the ground. We are, therefore optimistic that many of the barriers are more addressable than many perceive. And that much more can be done today to reduce gas flaring.

We also asked our surveyees “what other thoughts or ideas would you like to share?” and from the range of ideas from which we distilled 5 main recommendations:

- Governments must improve the economic incentives: Governments have a role in determining the economic environment, including areas such as fiscal policy, gas entitlement, flaring penalties, carbon taxes. They can also set standards and help in infrastructure building.

- Regulators need to be more effective: Many respondents highlighted the importance of the regulator to collect data and then act. We’ve seen a few too many examples where the regulator relies on the NOC to provide flaring data and offers no independent challenge or enforcement (and is therefore ineffective in the application of penalties). Regulators can also intervene to make more effective use of spare capacity in pipelines.

- Companies need to be more innovative: creative thinking around flare aggregation/clustering, technology application, development of new markets (e.g. LPG for cooking or via CNG “virtual pipelines”), low-cost and modular solutions and commercial structuring also play a key role. Capterio’s unique “Global Flaring Intelligence Tool” (GFIT) enables our partners to define projects with critical mass.

- New operating models and solution providers should be encouraged: Several respondents commented on the need for innovation in the way the industry tries to solve the gas flaring challenge. Scalable solutions that utilise proven technology and build local content are key. Especially in today’s world of low reduced capital budgets and a focus of “doing more with less”, IOCs and NOCs are looking to capitalise on third-party solutions with a proven track record.

- We need to accelerate the mindsets shift towards a no-flaring culture, driven by ESG, sustainability and investability concerns. Several respondents commented on the importance of attitudes, top-down leadership and a culture of excellence as being an enabler of flare reduction programmes. As an employee in a US major said, “we should think about flaring as a constraint, like we do with permitting. We don’t consider permitting a barrier, we work with it”.

It is true that perceptions matter. But this survey also identified that not all perceptions are entirely accurate. We believe that flare reduction can and must be much quicker in this critical next decade. Let’s work together to turn perceptions into reality.

For more information about this survey or about the work of Capterio, please contact mark.davis@capterio.com.